By Justin Fundalinski, MBA | July 20, 2018

Several years ago, I wrote an article about the changes coming in 2018 on income related Medicare premiums. Better known as the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (or IRMAA), this provision of Medicare rears its head and increases Medicare premiums as individual or couple’s income rises. It’s essentially an added tax, or a way to help fund an underfunded Medicare program.

Several years ago, I wrote an article about the changes coming in 2018 on income related Medicare premiums. Better known as the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (or IRMAA), this provision of Medicare rears its head and increases Medicare premiums as individual or couple’s income rises. It’s essentially an added tax, or a way to help fund an underfunded Medicare program.

In the article I discussed the coming changes and how the income thresholds used to determine whether someone is subject to increased Medicare premiums are normally adjusted for inflation. Generally, as a retiree’s income naturally grows due to inflation they are not forced over higher thresholds and thus higher Medicare premiums. At the time of the article those brackets had been intentionally frozen (under the Affordable Care Act) to slowly force more people into higher premiums between the years 2011 and 2019. However, while the thresholds are still frozen (and always subject to extension), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (Trump Tax Reform) made some notable changes that require an update and some review.

Changes as of 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act

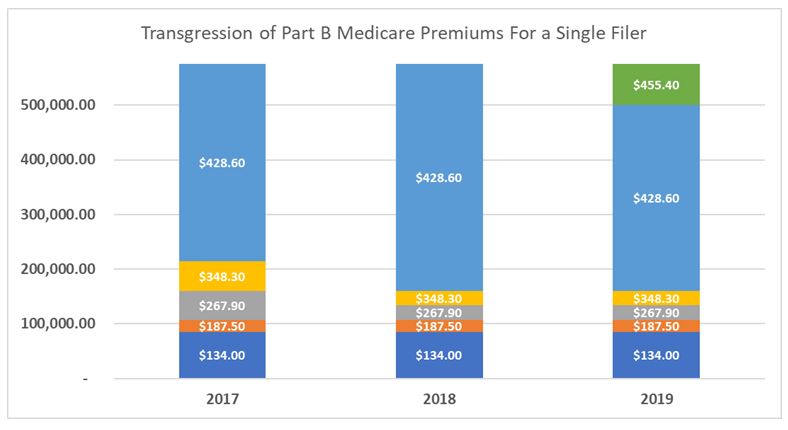

Most notably, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 piled on top of the changes that took effect in 2018 and added an additional threshold/tier of surcharges that will be introduced in 2019. Currently, there are five different Medicare premium levels based on the income levels of the Medicare recipient. In 2019 there will be six.

The graph above outlines the transgression of Medicare Part B premiums from 2017 through 2019. It illustrates what premium you would pay in 2017, 2018, and 2019 dependent on the amount of Modified Adjusted Gross income you have. You can see how from 2017 to 2018 the thresholds that force people into higher Medicare Premiums began to be compressed into lower thresholds once income was greater than $133,500 (this was discussed in detail in the previous article). From 2018 to 2019 they will be maintaining those compressed thresholds but also adding a new tier of premiums once income is beyond $500,000.

The graph above outlines the transgression of Medicare Part B premiums from 2017 through 2019. It illustrates what premium you would pay in 2017, 2018, and 2019 dependent on the amount of Modified Adjusted Gross income you have. You can see how from 2017 to 2018 the thresholds that force people into higher Medicare Premiums began to be compressed into lower thresholds once income was greater than $133,500 (this was discussed in detail in the previous article). From 2018 to 2019 they will be maintaining those compressed thresholds but also adding a new tier of premiums once income is beyond $500,000.

Married Filing Jointly

What is interesting about the new 2019 brackets is when you look at them for someone who files their taxes married filing jointly. In all previous cases, the thresholds illustrated here for a single filer would double for a married couple. However, to reach the highest threshold in 2019 as a married filing jointly person your income will have to be greater than $750,000 (not $1,000,000 had the normal trend followed suit). That’s only a 1.5X increase instead of the normal 2X. I interpret that as a penalty for being married.

Although, this won’t affect most households it is important information to know. Why? Well if these thresholds continue to be frozen, then over time more and more people will be forced into higher premium levels simply because their income grew with inflation (this is above and beyond the normal adjustment for increased insurance costs). Currently, the thresholds are scheduled to begin getting adjusted for inflation again in 2020, however I wouldn’t count on it. My argument on why I believe this is thoroughly outlined in a previous article I wrote in 2016 called, “Trickle-Down Taxes” In this article I argue how sneaky policy that is presented to tax the rich is really designed to very slowly increase taxes on the masses.

If you have any questions or comments on this article, please feel free to reach out to the office.

In a previous article I discussed in detail the intricacies of

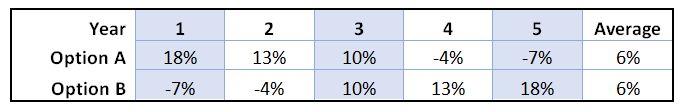

In a previous article I discussed in detail the intricacies of  “Sequential risk” or “sequence of returns risk” is a well-defined and highly discussed term in the retirement planning and investment industry. Under certain circumstances it can be one of the largest risks pre-retirees and early retirees face. Much of the basis of our firm’s retirement planning strategies is formed around managing this risk, and the highly recognized “4% withdrawal rate rule” was developed in lieu of this risk. Unfortunately, many who are reaching retirement or already retired simply don’t understand sequential risk, and do not place enough weight on managing it effectively. In this month’s article I intend to define in simple terms what sequential risk is and hopefully inspire people to take action.

“Sequential risk” or “sequence of returns risk” is a well-defined and highly discussed term in the retirement planning and investment industry. Under certain circumstances it can be one of the largest risks pre-retirees and early retirees face. Much of the basis of our firm’s retirement planning strategies is formed around managing this risk, and the highly recognized “4% withdrawal rate rule” was developed in lieu of this risk. Unfortunately, many who are reaching retirement or already retired simply don’t understand sequential risk, and do not place enough weight on managing it effectively. In this month’s article I intend to define in simple terms what sequential risk is and hopefully inspire people to take action.

With the new tax law doubling the standard deduction it is going to be much harder to itemize your tax deductions. Unfortunately, for those who give to charities this change may cause their charitable gifts to be far less valuable from a tax prospective. However, there is an excellent way to give to qualified charities as well as reduce your taxable income if you are over 70½. If you haven’t already, it’s time to start making Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) from your IRA.

With the new tax law doubling the standard deduction it is going to be much harder to itemize your tax deductions. Unfortunately, for those who give to charities this change may cause their charitable gifts to be far less valuable from a tax prospective. However, there is an excellent way to give to qualified charities as well as reduce your taxable income if you are over 70½. If you haven’t already, it’s time to start making Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) from your IRA. Considering the reader base of this newsletter, I assume most reading this are attempting to be good savers for retirement and are patting themselves on the back each year for peeling off portions of their earned income to save into 401(k)s and IRAs, all while reducing their current year’s tax bill. I commend you for your discipline and urge you to look even deeper into the future. As we all know the only thing guaranteed in life is death and taxes. While we can’t help you with death (perhaps my wife could as a Board Certified Palliative and Hospice Nurse Practitioner), I do think we can help reduce the tax liability you are creating for yourself in the future when you defer those taxes by saving into accounts like 401(k)s and Traditional IRAs.

Considering the reader base of this newsletter, I assume most reading this are attempting to be good savers for retirement and are patting themselves on the back each year for peeling off portions of their earned income to save into 401(k)s and IRAs, all while reducing their current year’s tax bill. I commend you for your discipline and urge you to look even deeper into the future. As we all know the only thing guaranteed in life is death and taxes. While we can’t help you with death (perhaps my wife could as a Board Certified Palliative and Hospice Nurse Practitioner), I do think we can help reduce the tax liability you are creating for yourself in the future when you defer those taxes by saving into accounts like 401(k)s and Traditional IRAs. Admittedly, this overview of Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) is designed to be quick and concise. There are far too many tangents that can be covered in a simple newsletter such as this, and the point of this article is not to educate you on every detail, but to get you thinking whether taking advantage of NUA makes sense financially.

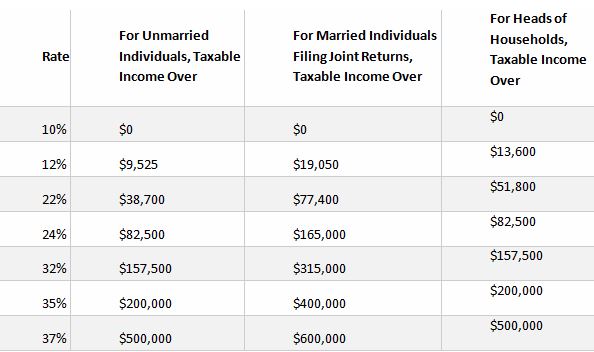

Admittedly, this overview of Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) is designed to be quick and concise. There are far too many tangents that can be covered in a simple newsletter such as this, and the point of this article is not to educate you on every detail, but to get you thinking whether taking advantage of NUA makes sense financially. In the most overtly sarcastic manner, I’m sure that you are all clamoring to read the new 1097 page Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Lucky for you I have been actively reading through the portions of it that will affect most people. Below are some bullet points you can peruse through, but if you really want to get in to the dirt the full bill can be found here.

In the most overtly sarcastic manner, I’m sure that you are all clamoring to read the new 1097 page Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Lucky for you I have been actively reading through the portions of it that will affect most people. Below are some bullet points you can peruse through, but if you really want to get in to the dirt the full bill can be found here.

Considering many people’s 401(k)s are usually one of their largest retirement savings assets and many 401(k) providers offer the ability to borrow money, it can be very enticing to take out a loan from your 401(k) to help fund your next big purchase. 401(k) loans are quick, easy, and do not need a credit check. Unfortunately, there are some downsides to borrowing money from a 401(k) and understanding certain issues can help you make the right lending decisions as well as potentially avoid steep tax consequences. Particularly in this article I will focus on what happens when a 401(k) loan defaults and what options you have.

Considering many people’s 401(k)s are usually one of their largest retirement savings assets and many 401(k) providers offer the ability to borrow money, it can be very enticing to take out a loan from your 401(k) to help fund your next big purchase. 401(k) loans are quick, easy, and do not need a credit check. Unfortunately, there are some downsides to borrowing money from a 401(k) and understanding certain issues can help you make the right lending decisions as well as potentially avoid steep tax consequences. Particularly in this article I will focus on what happens when a 401(k) loan defaults and what options you have. Are you receiving Social Security income, taking withdrawals from your IRA’s, or receiving a pension from a past employer? Well, as a Colorado resident you could have some tax benefits on this income. Under Colorado tax code you may be able avoid including some (or all) of this income as taxable income on your Colorado tax return. Let’s dig into some of the details.

Are you receiving Social Security income, taking withdrawals from your IRA’s, or receiving a pension from a past employer? Well, as a Colorado resident you could have some tax benefits on this income. Under Colorado tax code you may be able avoid including some (or all) of this income as taxable income on your Colorado tax return. Let’s dig into some of the details.