By Scott Roark, MBA, PhD | April 17, 2020

When it comes time to start living off the investment accounts you’ve spent a lifetime building up, there are some choices that can help you manage your taxes. The rest of this article presumes that you have taxable brokerage investments – such as stocks, ETFs or mutual funds that are not part of retirement accounts. Of course, any distributions from a retirement account, such as an IRA or 401k, will be taxable as ordinary income and the only choice you have is how much to withdraw.

In a taxable account, however, there are some other considerations. This is because any time you sell a holding, the IRS will want to know what the tax consequence of that sale is. There are three possible scenarios:

- The first possibility is that you sell some shares of your investment for exactly the same price that you paid for those shares. In this case, there is no taxable gain or loss and so there is no effect on your taxes. All the proceeds of the sale are available for whatever use you desire.

- A second possibility is that you sell some shares of your investment for less that you paid for those shares. In this case, you have a loss that can be used to offset gains on other investments you sell or the loss can offset up to $3,000 of otherwise taxable income.

- The third possibility is that you sell some shares of your investment for more than you paid for those shares. In this case, you have a capital gain. Depending on how long you have held those shares, you have either a short-term capital gain (taxed at your ordinary rate) or a long-term gain (taxed at lower rates).

With those scenarios as background, there is one important choice you can make with your brokerage account that can help you manage your tax situation. That is the choice on the cost basis. The cost basis refers to how much was paid for a particular share. In many accounts, particularly those with mutual funds where distributions from the mutual fund company are reinvested, there are many different transactions that occur over time. For instance, if you purchase 1000 shares of an S&P 500 index on January 1 and you have elected to have any distributions from the fund reinvested, there will likely be four additional purchases of shares in your account over the course of a year. This is because many of the S&P 500 firms pay dividends and these are passed through to mutual fund owners – usually on a quarterly basis. In addition, many investors make periodic purchases by adding new money to an account over time. So in any account with mutual funds, there are likely a rather large number of separate transactions to buy shares.

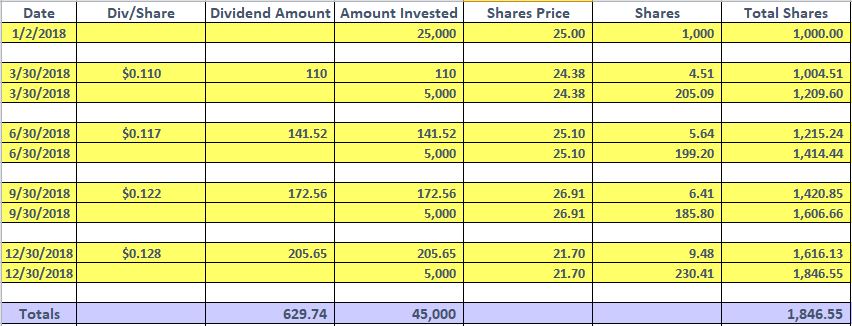

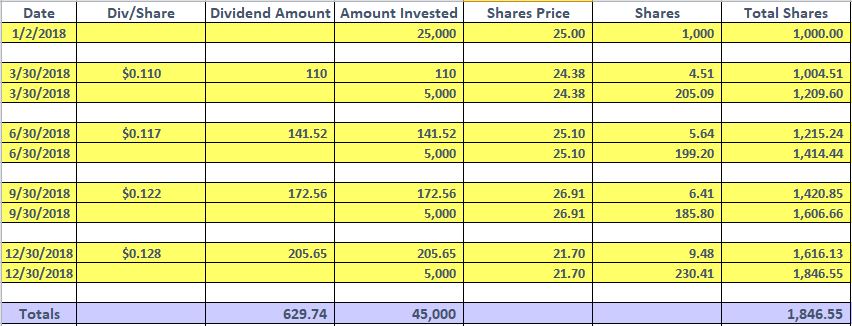

Because these shares have been purchased at different times throughout the year, there is likely a different purchase price (and cost basis) for each transaction. In the example outlined above, there is the initial purchase, the quarterly reinvestments and the quarterly additions of new money. In all, there are nine transactions in this simple account. Let’s walk through the spreadsheet below and look in more detail at these transactions. We will need this example in order to make sense of the choices an investor has when we discuss these choices later.

Here is a numerical example (roughly modeled on 2018 when there were sizable fluctuations in the market over the year):

Jan 2 – Investor makes an initial purchase of $25,000 for $25.00 per share. The investor has a total of 1,000 shares.

Here is a numerical example (roughly modeled on 2018 when there were sizable fluctuations in the market over the year):

Mar 30 – The investor receives a dividend of $0.11 per share. This is $110 and they can reinvest and get 4.51 shares at the new price of $24.38. In addition, the investor puts in $5,000 of new money in and gets 205.09 additional shares. The new share total is 1,209.60.

June 30 – Dividend of $0.117 per share. The dividend is $141.52 (equal to 1209.60 shares x $0.117 per share). This is reinvested at the new price of $25.10 and results in 5.64 new shares. In addition, the investor puts in $5,000 of new money and gets 199.20 shares for a new total of 1414.44 shares.

Sept 30 – Dividend of $0.122 per share. The dividend is $172.56 and at the new price of $26.91 per share, the reinvestment results in 6.41 new shares. The investor also adds $5,000 of new money and gets 185.80 new shares for a total of 1606.66 shares.

Dec 30 – Dividend of $0.128 per share. With the share total of 1606.66, the dividend is 205.65 and after a deterioration in the share price, the dividend reinvestment results in 9.48 new shares (at the new price of $21.70 per share). With the addition of $5,000 of new money, the investor also gets 230.41 additional shares. The total shares at the end of the year is now 1,846.55.

The total invested over the year comes in 3 flavors: the initial purchase (of $25,000), the additional contributions of $5,000 per quarter (total of $20,000) and the reinvested dividends which total $629.74. The cumulative invested over the year is $45,629.74.

Now to the choice you can make to help manage taxes. There are 3 main alternatives to determining the cost basis of the mutual fund shares you sell from your taxable account: average cost, FIFO and specific share identification.

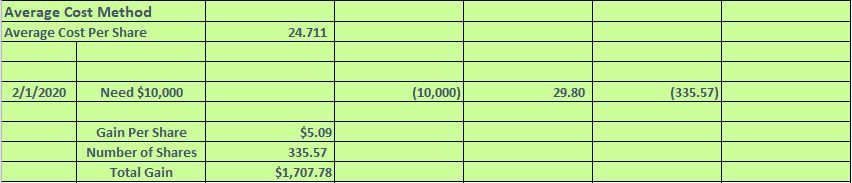

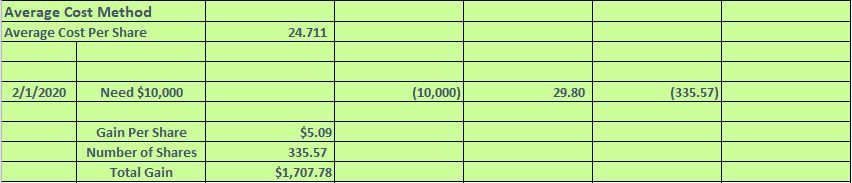

- Average cost means that all of the shares are treated as coming from one big bucket and the cost basis for each share is the average price paid for all the shares in the bucket (including any reinvested dividends or capital gains). In the example, this would mean the average cost per shares is $45,629.74 ÷ 1846.55 shares = $24.711 per share. Whenever a share is sold, its cost basis will be considered $24.711 per share.

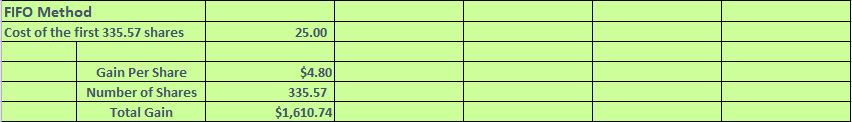

- FIFO is short for “First In, First Out”. This means that the oldest shares are sold first. In the example provided, any number of shares sold up to the initial 1000 purchased will have a cost basis of $25.00 per share. After those first 1000 shares are sold, the next 209.60 shares will have a cost basis of $24.38 per share. After that will be 204.84 shares with a cost basis of $25.10, etc.

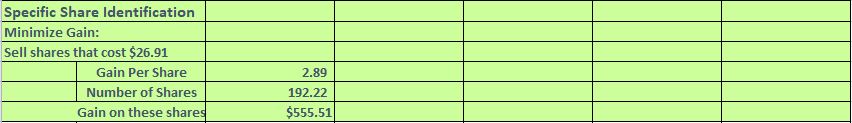

- Specific share identification means that you tell your brokerage firm which shares to sell – you “specify” the shares. The cost basis for the shares you sell will depend on which shares you specify. You have some shares that have a cost basis of $25.00, some at $24.38, some at 25.10, etc.

Here is how your choice of cost basis makes a difference. Let’s say you needed $10,000 on February 1, 2020 – when the share price of your S&P 500 index fund is $29.80 per share. You will need to sell $10,000 ÷ 29.80 = 335.57 shares to get that money.

If your choice of cost basis is Average Cost, then for each share you sell, you will have (29.80 – 24.711) in capital gains. In this case the total gain is $1,708 and you would pay long-term capital gains rates on this for your taxes.

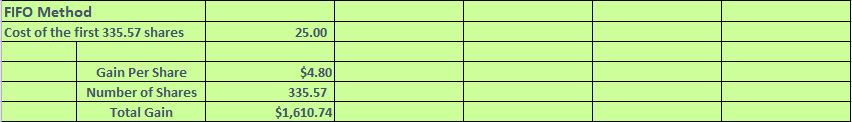

If your choice of cost basis is FIFO, then for each share you sell, you will have (29.80 – 25.00) in capital gains. In this case the total gain is $1,611.

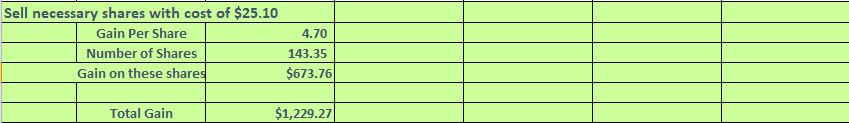

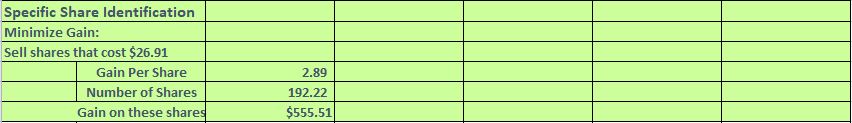

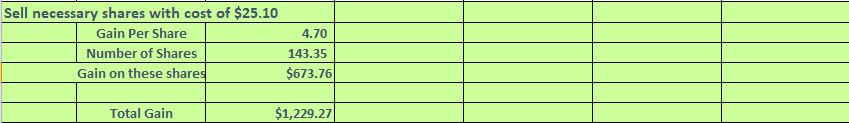

If your choice of cost basis is Specific Share Identification, you have more flexibility. If you want the lowest possible tax hit, you can choose to sell the highest cost shares first. In this case, you still need to sell 335.57 shares and you can do that by selling 192.22 share you bought at $26.91 per share and sell the remaining shares (143.35) which have a cost basis of $25.10. In this case, your gain will be only $1,229 – potentially saving you a few hundred dollars in taxes in the current year.

One quick point worth mentioning here. If you sold ALL of the shares in any given year, the amount of the taxable gain will be EXACTLY the same. The only thing that is changing when you select different methods is the timing of the taxes.

The big takeaway from all of this is that investors have a choice as to which cost basis method they use. The default is likely the Average Cost Method or the FIFO method, depending on your brokerage firm. However, the Specific Share Identification Method provides the most flexibility in managing your tax situation when selling shares from your brokerage account. In order to change methods, you likely only need to go online and make a selection of “Specific Share ID” and you are set. Then when it comes time to sell some of your holdings, you select which shares to sell in order to best manage your tax situation.