By Scott Roark, MBA, PhD | August 2, 2019

What Is Sequence Risk?

Sequence risk is an important notion in the world of retirement planning. It refers to the risk that the sequence of returns in an investment portfolio will negatively impact the ability of the portfolio to deliver sufficient payouts throughout retirement. In extreme circumstances, sequence risk may even mean a portfolio runs out of assets too soon.

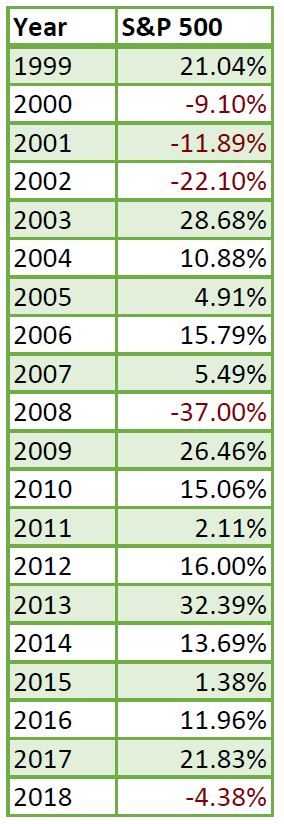

Let’s look at the past 20 years of returns (including reinvested dividends) for the S&P 500 for example1:

The average rate of return for these 20 years is 7.16%.

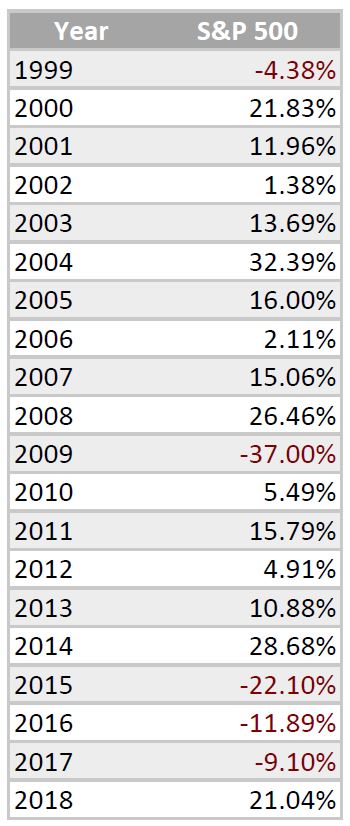

Now consider the exact same returns, now with the returns occurring in the reverse order1:

The average rate of return for this hypothetical, alternate set of returns is also 7.16%, exactly the same as for the original set of returns. With a static portfolio (where you are neither putting money in nor taking money out), you would have the exact same ending portfolio value under either scenario.

However, if you are in retirement and withdrawing from the assets, the sequence of returns has a dramatic effect on the portfolios. Assume that you have a $1,000,000 at the start of retirement and that you will take out $40,000 at the start of the first year (4% withdrawal rate) to support your annual spending. Each year, your withdrawal will increase by inflation (let’s assume 2.5%) to cover the increased costs of the goods and services you consume.

For the actual series of returns from 1999-2018, you would end up with a portfolio value of about $660,000. For the hypothetical reverse order returns, the portfolio value after 20 years would be about $1,460,000 – more than twice as large as before. Keep in mind that NOTHING has changed except the order of returns that the market experienced. This gives some indication of the power of sequence risk when a portfolio is being consumed.

To take the example one step further, let’s pretend that retirement started not 20 years ago – but 19 years ago in January 2000 (right when the market was about to enter a three-year tailspin). We’ll still start with $1,000,000 and still withdraw 4% of the account ($40,000) in the first year and then grow that amount by 2.5% inflation. Now that portfolio has shrunk to $318,000 after 19 years. And if we had accidentally decided we could afford a 4.6% withdrawal rate back in 2000 ($46,000 for that first year’s withdrawal) – the account would have hit $0 with our 2018 withdrawal. On the other hand, our “alternate universe” portfolio – with the reversed returns – would have ended 2018 with over $1.5 million using the same set of assumptions.

The Lesson For Retirement Planning

Given these relatively straightforward assumptions, you can see how big of an impact the series of returns can have on a portfolio. While there is never really a good time to have a bad year of returns, the sooner the bad returns happen after retirement, the worse it is for a portfolio.

There are a host of interesting observations one can make looking at historical returns, in considering different portfolio constructions (100% bonds, 50% bonds/50% stocks, 100% stocks) and different withdrawal rates. One of the important takeaways (which we may explore further in a future post) is the importance of having some principal-protected assets for the early years of retirement along with a well-diversified portfolio. Those two components of a retirement plan go a long way towards mitigating the dangers of sequence risk.

1Sources: https://ycharts.com/indicators/sp_500_total_return_annual ; https://www.slickcharts.com/sp500/returns